As a native of the low country, I love showcasing and teaching everyone about my upbringing and culture. One of the most important parts of low country culture in Georgia and South Carolina is the Gullah Culture. From the foods we eat (rice, shrimp and grits and more), the bold coastal art, A�to the religious tradition, Gullah Culture is infused with everything. If you want to learn more about this unique culture, check out theA�5 Books on Gullah Culture That We Love.A�These books are a great way to learn more without making a trip to the lowcountry, although we certainly hope you do!

5 Books on Gullah Culture That We Love

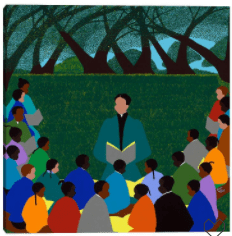

Gullah Culture in America begins with the journeys of 15 Gullah speakers who went to Sierra Leone and other parts of West Africa in 1989, 1998, and 2005 to trace their origins and history. Their stories frame this fascinating look at the extraordinary history of the Gullah culture. The existence of the Gullahs went almost unnoticed until the 1860s, when missionaries from Philadelphia made their way to St. Helena Island, South Carolina, to establish the Penn School to help freed slaves learn to read and write. There, they discovered hidden pockets of a bygone African culture with its own language, traditions, medicine, weaving, and art. Today, more than 300,000 Gullah people live in the remote areas of the sea islands of St. Helena, Edisto, Coosay, Ossabaw, Sapelo, Daufuski, and Cumberland, their way of life endangered by overdevelopment in an increasingly popular tourist destination. Having evolved from the original Penn School, the Penn Center, based on St. Helena Island, works to preserve and document the Gullah and Geeche cultures. Author Wilbur Cross originally set out to make the excellent work of the Penn Center known and to introduce the Gullah culture to people in America. He became entranced with the Gullah way of life and ended up with 12 chapters that explore the various facets of Gullah culture. Gullah Culture in America not only explores the history of Gullah but also shows readers what ita��s like to grow up and live in this unique American community.

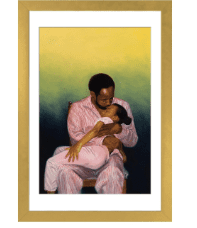

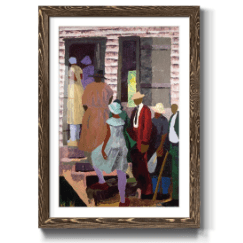

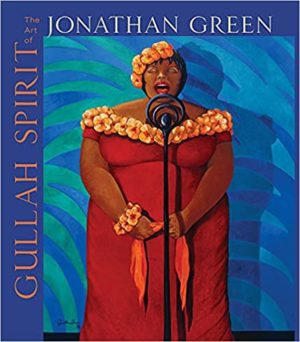

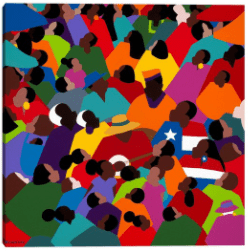

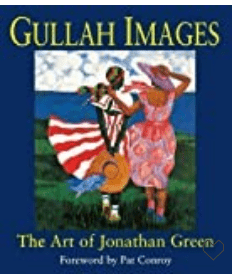

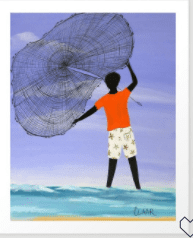

Gullah Images: The Art of Jonathan Green

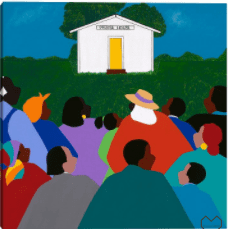

In his art Jonathan Green paints the world of his childhood and an ode to a people imbued with a profound respect for the dignity and value of others – the Gullah people of the South Carolina barrier islands. His vibrant canvases, beloved for their sense of jubilation and rediscovery, evoke the meaning of community in Gullah society and display a reverence for the rich visual, oral, and spiritual traditions of its culture. His art reveals a keen awareness of the interpersonal, social, and natural environments in which we live.

Making Gullah: A History of Sapelo Islanders, Race, and the American Imagination

During the 1920s and 1930s, anthropologists and folklorists became obsessed with uncovering connections between African Americans and their African roots. At the same time, popular print media and artistic productions tapped the new appeal of black folk life, highlighting African-styled voodoo as an essential element of black folk culture. A number of researchers converged on one site in particular, Sapelo Island, Georgia, to seek support for their theories about “African survivals,” bringing with them a curious mix of both influences. The legacy of that body of research is the area’s contemporary identification as a Gullah community.

This wide-ranging history upends a long tradition of scrutinizing the Low Country blacks of Sapelo Island by refocusing the observational lens on those who studied them. Cooper uses a wide variety of sources to unmask the connections between the rise of the social sciences, the voodoo craze during the interwar years, the black studies movement, and black land loss and land struggles in coastal black communities in the Low Country. What emerges is a fascinating examination of Gullah people’s heritage, and how it was reimagined and transformed to serve vastly divergent ends over the decades.

If there’s one thing we learned coming up on Daufuskie,” remembers Sallie Ann Robinson, “it’s the importance of good, home-cooked food.” In this enchanting book, Robinson presents the delicious, robust dishes of her native Sea Islands and offers readers a taste of the unique, West African-influenced Gullah culture still found there.

Living on a South Carolina island accessible only by boat, Daufuskie folk have traditionally relied on the bounty of fresh ingredients found on the land and in the waters that surround them. The one hundred home-style dishes presented here include salads and side dishes, seafood, meat and game, rice, quick meals, breads, and desserts. Gregory Wrenn Smith’s photographs evoke the sights and tastes of Daufuskie.

“Here are my family’s recipes,” writes Robinson, weaving warm memories of the people who made and loved these dishes and clear instructions for preparing them. She invites readers to share in the joys of Gullah home cooking the Daufuskie way, to make her family’s recipes their own.

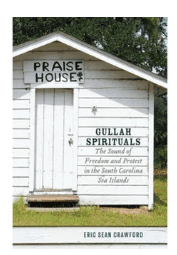

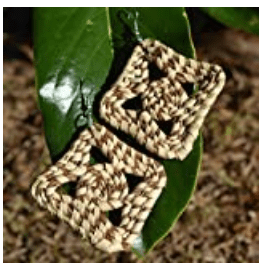

Talking to the Dead: Religion, Music, and Lived Memory among Gullah/Geechee Women

Talking to the Dead is an ethnography of seven Gullah/Geechee women from the South Carolina lowcountry. These women communicate with their ancestors through dreams, prayer, and visions and traditional crafts and customs, such as storytelling, basket making, and ecstatic singing in their churches. Like other Gullah/Geechee women of the South Carolina and Georgia coasts, these women, through their active communication with the deceased, make choices and receive guidance about how to live out their faith and engage with the living. LeRhonda S. Manigault-Bryant emphasizes that this communication affirms the women’s spiritual faitha��which seamlessly integrates Christian and folk traditionsa��and reinforces their position as powerful culture keepers within Gullah/Geechee society. By looking in depth at this long-standing spiritual practice, Manigault-Bryant highlights the subversive ingenuity that lowcountry inhabitants use to thrive spiritually and to maintain a sense of continuity with the past.