As a descendant of Black farmers and landowners, I have a special place in my heart for supporting Black farmers. One way to support black farmers is becoming one or advocating for them. I have compiled a few of my favorite books on black farming below and hope you will add them to your collection. If you know of any black farms in your area, be sure to share them with us by email at michiel@blacksouthernbelle.com or on social media using the hashtag #blacksouthernbelle

Black Farmers: Books On African American Farming To Add To Your Library

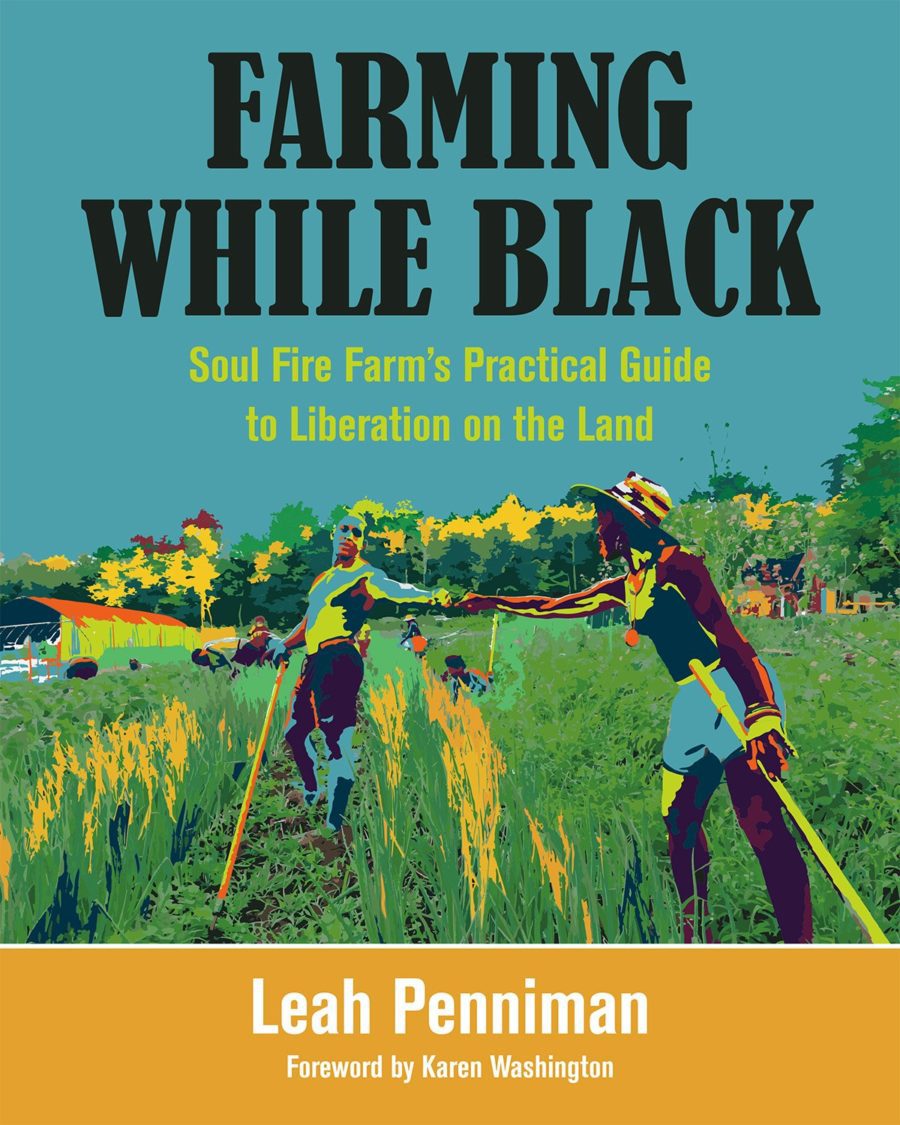

Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land

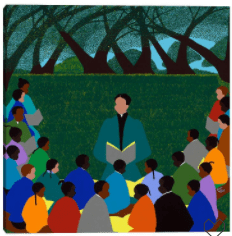

Farming While Black is the first comprehensive “how to” guide for aspiring African-heritage growers to reclaim their dignity as agriculturists and for all farmers to understand the distinct, technical contributions of African-heritage people to sustainable agriculture. At Soul Fire Farm, author Leah Penniman co-created the Black and Latinx Farmers Immersion (BLFI) program as a container for new farmers to share growing skills in a culturally relevant and supportive environment led by people of color. Farming While Black organizes and expands upon the curriculum of the BLFI to provide readers with a concise guide to all aspects of small-scale farming, from business planning to preserving the harvest. Throughout the chapters Penniman uplifts the wisdom of the African diasporic farmers and activists whose work informs the techniques described―from whole farm planning, soil fertility, seed selection, and agroecology, to using whole foods in culturally appropriate recipes, sharing stories of ancestors, and tools for healing from the trauma associated with slavery and economic exploitation on the land. Woven throughout the book is the story of Soul Fire Farm, a national leader in the food justice movement.

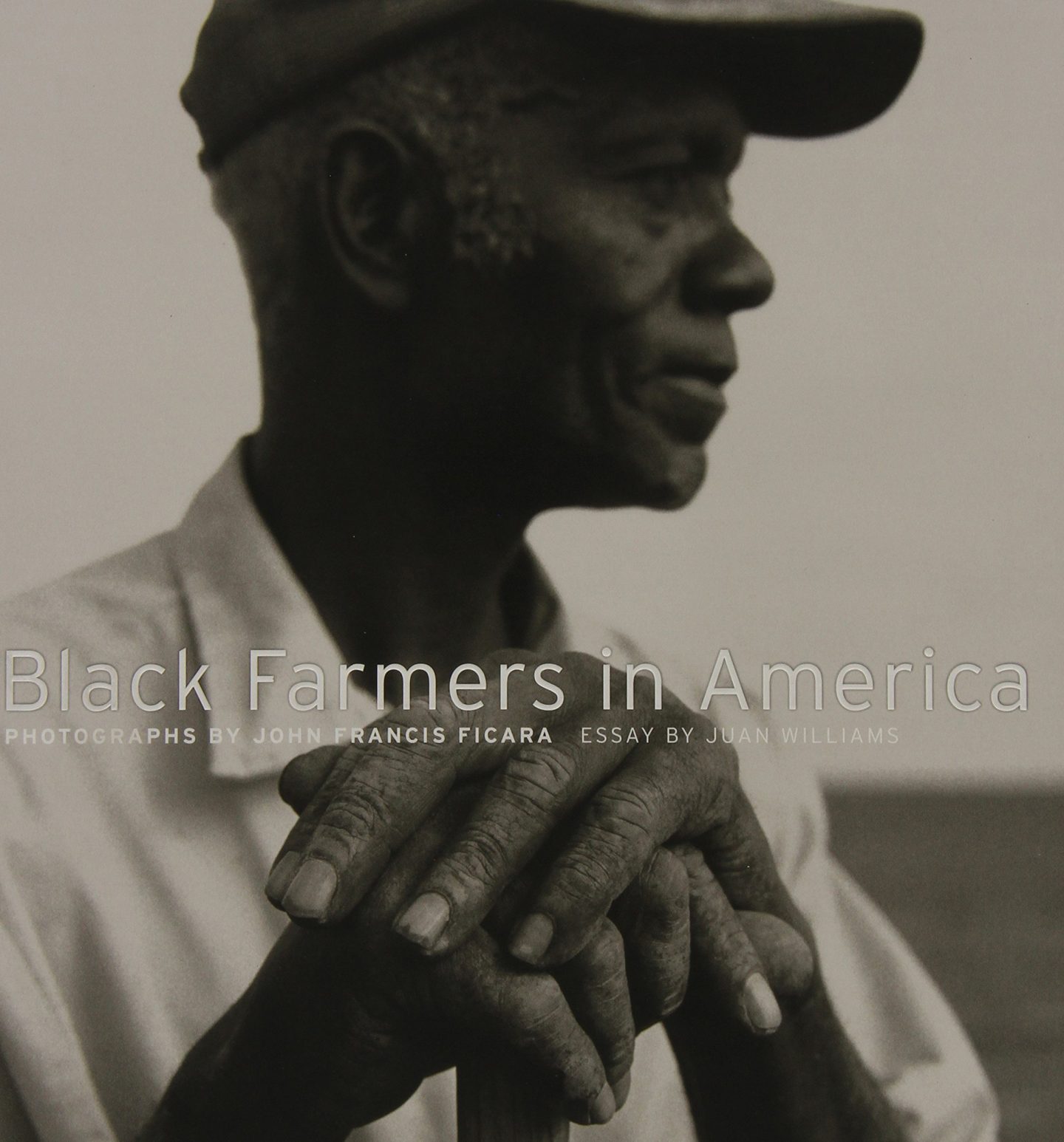

Homecoming: The Story of African-American Farmers

An illustrated history of African-American farmers, Homecoming is a requiem for a way of life that has almost disappeared.

Based on the film Homecoming, produced for the Independent Television Service with funding provided by the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. The videocassette of Homecoming is available from California Newsreel at www.newsreel.org.

In Greene County, Alabama, a deserted farmhouse sits in the middle of a field so overgrown with weeds that the house is completely engulfed; snaking vines and stalks cover the doors and windows and invade the chimney, choking off any possibility of human habitation. Hidden by a curtain of greenery, the house stands as a silent testament to the loss that black American farmers and their families have endured during the twentieth century. What keeps these families from their dreams and way of life, however, is not the encroachment of natural forces but the demise of a culture that supports independent farmers. In 1920, black Americans made up 14 percent of all farmers in the nation, and they owned and worked 15 million acres of land. Today, battling the onslaught of globalization, changing technology, an aging workforce, racist lending policies, and even the U.S. Department of Agriculture, black farmers account for less than 1 percent of the nation’s farmers and cultivate fewer than 3 million acres of land

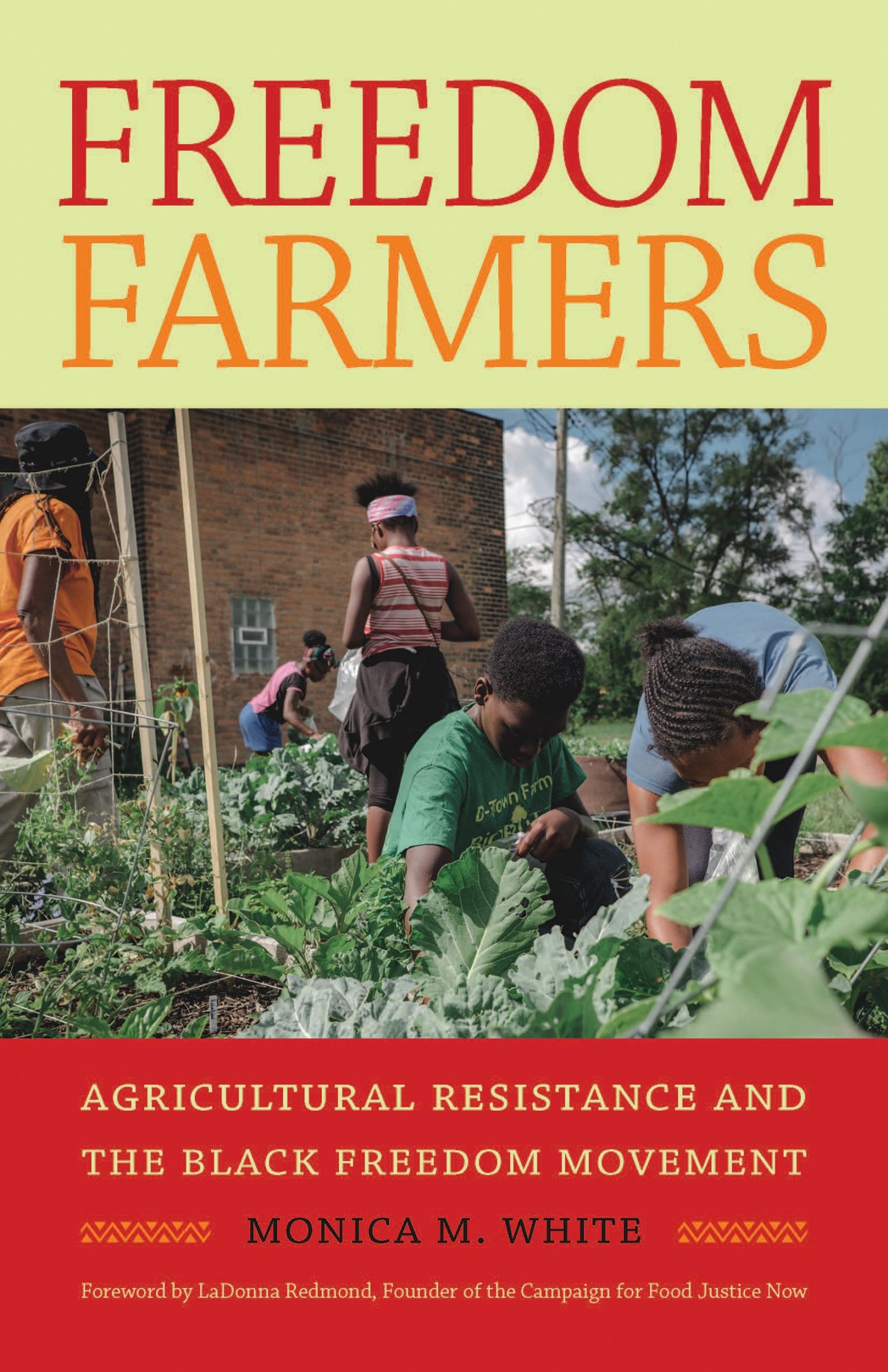

In May 1967, internationally renowned activist Fannie Lou Hamer purchased forty acres of land in the Mississippi Delta, launching the Freedom Farms Cooperative (FFC). A community-based rural and economic development project, FFC would grow to over 600 acres, offering a means for local sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and domestic workers to pursue community wellness, self-reliance, and political resistance. Life on the cooperative farm presented an alternative to the second wave of northern migration by African Americans–an opportunity to stay in the South, live off the land, and create a healthy community based upon building an alternative food system as a cooperative and collective effort.

Freedom Farmers expands the historical narrative of the black freedom struggle to embrace the work, roles, and contributions of southern black farmers and the organizations they formed. Whereas existing scholarship generally views agriculture as a site of oppression and exploitation of black people, this book reveals agriculture as a site of resistance and provides a historical foundation that adds meaning and context to current conversations around the resurgence of food justice/sovereignty movements in urban spaces like Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee, New York City, and New Orleans.