The Easter Rockers of Winnsboro LA Preserve a Generations-old Easter Eve Tradition

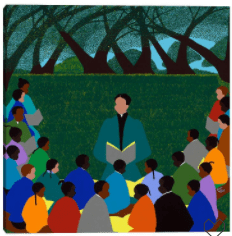

“We rock to a Risen Savior,” says Hattie Addison Burkhalter, the leader of what has been documented to be the oldest, and last remaining, Black women-led Easter Eve ritual. The Winnsboro Easter Rock Ensemble is based in the Northeast Louisiana Delta region in the town of Winnsboro, Franklin Parish, where most of the members reside. Mrs. Burkhalter was taught to rock by her mother and grandmother, who was taught by the generations before her. It is not a reenactment of something that happened long ago, it is a tradition that lives on.

In 2021, the Winnsboro Easter Rock Ensemble received The National Endowment for the Arts NEA National Heritage Fellowship, which includes an award of $25,000. The fellowship is the highest honor in the folk and traditional arts.

“The Rock,” as the vigil is called, begins on the Saturday before Easter during evening, and lasts about three hours. In the earliest days of The Rock, enslaved Africans and emancipated Blacks would begin the service at dusk and end it before sunrise on Easter Day. Mrs. Burkhalter says her mother taught her the importance of catching the sun as it rose to watch it “shout” or rock at the Risen Son. Another remaining vestige of original rocks is the church service that includes a sermon and music followed by The Rock and ending with a fellowship of cake and punch though the first rocks included a heartier communal dinner.

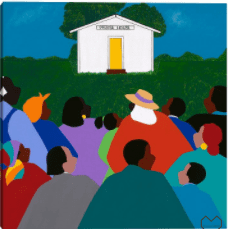

Original True Light Baptist Church near Winnsboro, the Addison family church, a recent home of the Easter Rock. Photo: Susan Roach.

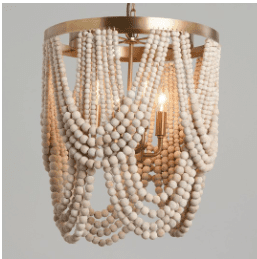

Symbolism flourishes in the Winnsboro Easter Rock. Even the punch, specifically red punch, and cake hold a meaning to the spiritual practice that includes the Christian Gospel merged with African movement and sound. The red punch and cake represent the blood and body of Jesus, and are sacrament of Holy Communion. A white-clothed rectangular table (Jesus’s tomb) will hold the punch and cake as well as 12 lit oil lamps representing the Twelve Tribes of Israel, which are placed on the table one at a time as rockers circle it for the first time. When they circle it a second time, they place twelve (white) cakes on the table, representing the 12 disciples. The punch follows with a basket of eggs symbolizing the opening of the Christ’s sepulcher or tomb.

Photo: Susan Roach, Louisiana Folklife Center

One of the most symbolic components shows up in the dress of the rockers. Women rockers wear uninterrupted white dresses or tops and skirts with white shoes. Male rockers wear white shirts and dark pants. White bears the meaning of purity, innocence and death.

Hattie Addison Burkhalter with the banner, leading the ensemble at a public presentation in Natchitoches, Louisiana. Louisiana Folklife Center, Marcy Frantom

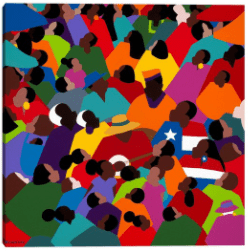

The first rocks were led by men and women, but in Winnsboro, rocks are led by an older woman as another elder woman flanks at the end. In between them are women and girls of varying ages. The first circle rocking counter-clockwise around the table, involves an all-woman group of rockers with men and boys allowed to join on rounds that follow. Mrs. Burkhalter states in presentations that women tend to lead, because it was women who first found Jesus’s empty grave.

The leader of the rock carries a banner that symbolizes Christ’s cross or Moses’s staff and is reminiscent of banners used in many West African funeral processions. During the antebellum period, enslaved women would shred up old fabrics and later use white sheets. Today’s banners are a combination of shredded white fabric and streamer paper on a circular platform or object, and they are four-five feet tall. Historian Susan Roach wrote, “To help the banner move from side to side, a ‘banner puller’ follows the banner carrier. Only certain members of the group can serve as banner puller since it takes strength and coordination to help control the large moving object.”

A remnant of the original rocks is the use of the body as instrumentation with handclaps and foot stomps on hardwood floors. Drums and other instruments were often prohibited on southern plantations, so the body was used to keep rhythm and make music.

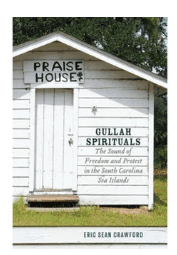

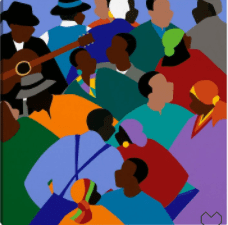

Similar to the Gullah-Geechee ring shout, rocking shares essential rules. The feet shuffle with the exception of stomps but are never raised too high off of the floor or cross so as not to confuse the dance with secular dance. One slight difference is the allowance for individual expression (within the rules) in the ring or shout, which is true for Gullah-Geechee ring shouts. Rocking is a little more rigid in movement. However, the intention is the same and that’s to worship.

Rockers sing hymns, relying on songs by Dr. Watts as well as call and response. The women generally enter The Rock singing in a capella, “When the Saints Go Marching In,” and exit one-by-one, singing “Oh, David.”

The ensemble has presented rocks in New Orleans at the Jazz and Heritage Festival, the Smithsonian in Washington DC and at other cultural festivals around the country.

To learn more about the Winnsboro Easter Rock Ensemble:

(Video) Winnsboro Easter Rock Ensemble: NEA National Heritage Fellows Tribute Video

(Video) The Winnsboro Easter Rock Ensemble: Louisiana Folklife Center

(Article) The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 55, No. 218, Oct. – Dec., 1942

(Forum) Civil War Talk, Louisiana Easter Traditions

“Everyone Rockin’ Together”: Continuity and Creativity in the Louisiana Delta Easter Rock, By Susan Roach [Photo Credit: Louisiana Folklife Center, Facebook]