The preeminent Black journalist and educator, Bill Maxwell, wrote about being a kid counting the days until he was old enough to go to Junior’s, a juke joint in Webster, Florida. He described the backwoods establishment with vivid detail. “In the kitchen, Mrs. Junior, as we called her, cooked delicious chicken, fish, pork chops, gopher tortoise, greens and french fries,” he wrote. Junior’s had seven rooms, the largest room was the bar or place where people bought their moonshine or bootlegged liquor. They danced to live music in the living room and ate at a counter on the back porch. In his words, Junior’s “was a place to party.”

Black women like Mrs. Junior have owned and operated juke joints and like establishments selling beer and liquor (legal and illegal), food and music, for generations. The music was the draw but devoted fans returned again and again for the perks like community, food and liquor. All of which were important to blues and jazz artists looking for venues to play and earn a dime.

In her essay, “Characteristics of Negro Expression,” Zora Neale Hurston wrote, “Musically speaking, the Jook is the most important place in America. For in its smelly, shoddy confines has been born the secular music known as blues, and on blues has been founded jazz.” The women who owned or co-owned businesses on the Mississippi Blues Trail were influential in the promotion of the blues and jazz.

Some of the first “clubs” and “jukes” date back as far as the late 1890s and early 1900s, when sharecroppers working and living on the land of former plantations, created a precursor to juke joints called “plantation parties” and “all-night picnics” to entertain themselves with homemade whiskey (moonshine), food, gambling and live music. Mississippi Delta plantations like Dockery Farms are where Charley Patton, Robert Johnson, Howlin’ Wolf, John Lee Hooker and Roebuck “Pop” Staples lived, worked and played the blues. It was at these types of parties that women cooked but also handled the business side and much of their savvy evolved over time into the creation of inns, clubs and juke joints that they owned or co-owned throughout the Delta and beyond.

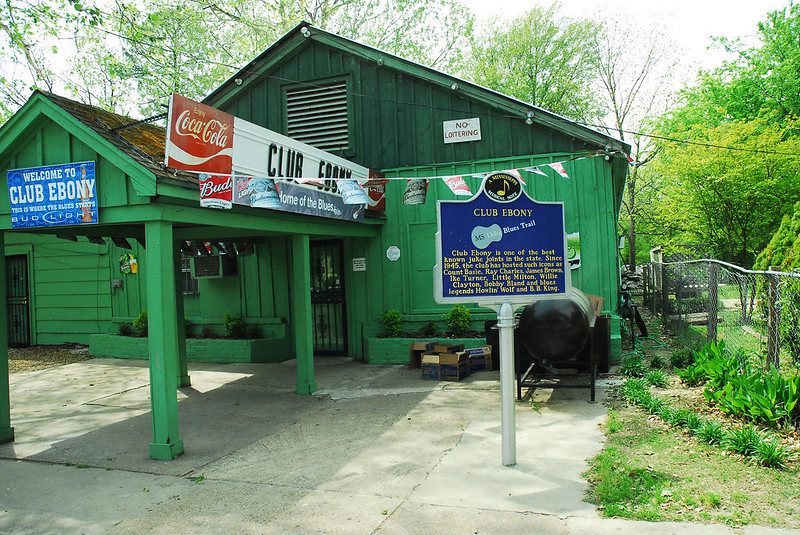

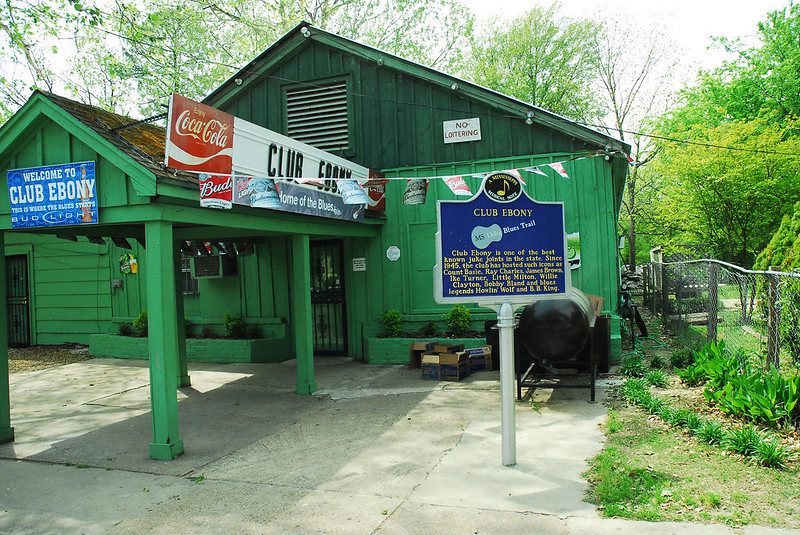

Club Ebony in Indianola, MS was one such club. The club was founded by Josephine and John Jones in 1948. Josephine and her son operated the business after John’s death “under the ownership of James B. ‘Jimmy’ Lee, a white bootlegger from Leland who had loaned money to Jones.” Lee turned over operations to Ruby Edwards, owner of Ruby’s Nite Spot, and by 1958, she was full owner when B. B. King married her daughter, Sue Carol Hall. Edwards was considered a shrewd businesswoman. Her dealings with Lee involved bootlegging and running after-hours parties that included gambling and the sale of alcohol. The extra money funded the high costs of bringing in big name artists such as Ray Charles, Bobby Bland, Junior Parker, Jimmie Lunceford, Big Joe Turner and Arthur Prysock. Later, Edwards rented Club Ebony to Willie and Mary Shepard, who would buy it from her in the 1970s. Mary Shepard, as sole owner (before selling the club to B. B. King) presented local blues artists in showcases.

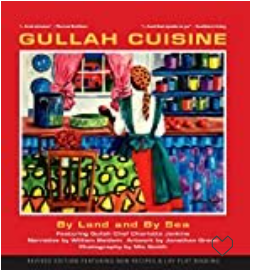

At Ruby’s Nite Spot in Leland, MS, “Crowds of hungry revelers dined on chicken, fish, hamburgers, and hot dogs and danced to the music of the country’s top names in blues as well as an impressive array of local and regional musicians. Ready to market anything that might sell, Edwards made tamales at one time and brewed her own corn liquor at another.” Ruby Edwards retired in the 1970s to run a family-owned grocery store. Her son took over the nightclub businesses.

Another Ruby, Ruby Patton, assisted her sons in taking over the Harlem Inn in Winstonville, MS, after her husband Hezekiah Patton, Sr. died in 1968 and a renter let the club go. With Hezekiah, Ruby and their sons built a blues club that featured entertainers like Ray Charles, Little Willie John, B. B. King, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Ivory Joe Hunter, T-Bone Walker, Howlin’ Wolf, The Impressions and Jackie Wilson. According to the Mississippi Blues Commission, “Jackie Wilson held an audience spellbound…when the club’s audience of five to six hundred outnumbered the population of Winstonville.” Sadly, a fire destroyed the venue in 1989.

NatalieMaynor from Jackson, Mississippi, USA – Blue Front Cafe

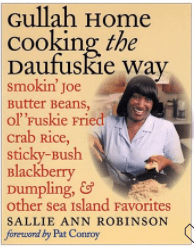

The Blue Front Café was owned by Mary and Carey Holmes from Bentonia. It was a multi-purpose operation serving as a café, down-home blues venue, grocery store, bar and barbershop. The Blue Front and their cotton crops enabled the couple to take care of 10 children and three nephews, sending most to college. Mary was the cook and managed operations while Carey worked their farm. The menu staples: fried buffalo fish, soda pop and moonshine. Musicians would pop up and perform without a formal invitation or schedule. The Holmes’s hosted outdoor gatherings on the family farm and musicians would come to play. Those gatherings later evolved into the Bentonia Blues Festival.

Two other women on the Mississippi Blues Trail were every bit as important as hotel and boarding house owners. Elma and W.J. Summers owned the Summers Hotel in Jackson, MS. The Summers Hotel was one of few places available for Black touring musicians to stay in Jackson. James Brown, Hank Ballard, andNat “King” Cole were among their guests. In a stroke of genius, the Summers’ with Jimmy King opened the Subway Lounge in the hotel’s basement, where they offered live jazz. By 1989, King and his wife Helen refashioned the Subway into a blues club.

Mrs. Z.L. Ratliff Hill, Riverside Hotel LLC

Mrs. Z.L. Ratliff Hill opened Clarksdale’s Riverside Hotel in 1944 and operated it until her death in the 1990s. Ike Turner lived there, writing and rehearsing “Rocket 88” before recording it at Sun Records. Sam Cooke, a Clarksdale native, is believed to have referred to the nearby Sunflower River in his hit record “A Change is Gonna Come.” John F. Kennedy, Jr. stayed there in 1991. Mrs. Ratliff cooked for every guest. The hotel’s history includes the fact that it was formerly the G.T. Thomas Afro-American Hospital, where blues legend Bessie Smith died. The Riverside Hotel is the only blues hotel that is still Black-owned in Clarksdale though it hasn’t been open since 2020, awaiting renovations. Mrs. Hill’s granddaughters and daughter-in-law have continued on as owners. They have a GoFundMe account to raise money for much-needed repairs.