This is the thirtieth anniversary of Spike Lee’s “Crooklyn.” The story was birthed and penned by Joie Lee’s memories of growing up in Brooklyn. One of the most incredible parts of the movie takes place in the South, where the Carmichael family drops off only-daughter Troy to spend the summer with Uncle Clem, Aunt Song and Cousin Violet. It’s an experience Troy has to lean into with effort, because life Down South is not nearly as stimulating as life in Brooklyn away from friends and family. Eventually, she and Violet forge a friendship rooted in a mutual irritation – Aunt Song and her ways. Aunt Song straightens Troy’s natural hair and attempts to prissy up Little Miss Carmichael’s wardrobe (and ways). Violet, for her part, tries to help Troy cope with Aunt Song, the nuances of southern living like religion and social norms of the era. And Song’s discovery of her beloved pooch Queeny’s untimely demise, bonded the viewer with Troy and Violet.

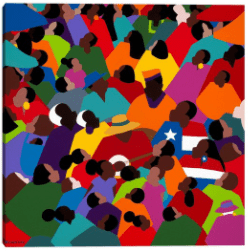

Black daughters and granddaughters of the Great Migration have been spending summers in the South with relatives for generations. For some, it was a rite of passage. Southern grannies and aunties make wonderful caregivers and companions – for the most part. The Aunt Song Experience is somewhere in the middle – a tolerable middle. Some stories are traumatic but many are nostalgic and warm. The stories below are an array of experiences.

“We played and got acquainted with cousins. We cooked, ate, listened to grown folk talking when we weren’t supposed to. We slept on pallets all over the house. There were always a bunch of us at one time,” says Philadelphia native Paulette Kendrick Gray, referring to visits to her mother’s hometown of Franklin, Virginia. She also recalls being closely watched by her Aunt Polly, who didn’t allow Paulette to wander off of the property. She did, however, keep her close enough to learn “how to can fruits and vegetables. My favorite was pickled watermelon rinds.”

St. Louis based Nancy Lewis says childhood trips to Mississippi (Plantersville and Nettleton, outside of Tupelo) were sometimes less than a week in length or for the entire summer. What remains with her is the family’s sense of community. “Something that was different is that my great grandparents and my aunt’s farms were actually like compounds with other relatives who had homes on the land. Another cousin lived across the road from my great-grandparents.”

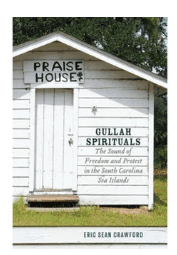

Bianca Gordon recalls learning about the environment and cultural heritage of the lowcountry, specifically her father’s Gullah-Geechee upbringing. “Being from a landlocked state, I think outside of noticing that my dad’s family spoke differently than what I was used to in Oklahoma, I remember being absolutely stunned that the sky and the Atlantic ocean seemed like one massive, majestic, continuous, blue body.”

She also notes that at her grandfather’s funeral, she heard something in the music. “I heard a different thing: a rhythmic clapping over ‘Amazing Grace.’ A triplet rhythm that moved the verses along. I’d never heard clapping during ‘Amazing Grace,’ much less a type of clapping.” (For an example of the hand clap and rhythm, watch Dance 111 – Ring Shout)

Jennifer Johnson’s recollections of southern summer visits with family in Arkansas are similar to the other women’s. But she mentioned a cultural shock that she had never experienced growing up in an urban city in Ohio. Happy to be going to the movies with her cousin, Jennifer and her sister headed towards the front entrance, when her cousin gently turned them in the direction of another entrance leading to the balcony. They had to abide by an uncomfortable and unspoken rule of that town long after Jim Crow had been federally outlawed. “Thankfully, we had our cousin to help us navigate the difficulty.”

Each woman talked about meeting family, performing chores, learning to cook from scratch, and the cultural differences between their homes and ‘home’ Down South. Nancy Lewis offers a revelation she had while visiting her family in Mississippi as an adult.

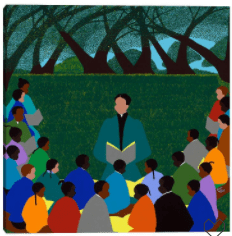

“Even though I wasn’t born there, I have always considered Mississippi home. This really came into focus when I returned for my grandmother’s sister’s funeral in the early 2000s. At the time, I was also working on my master’s and so part of my downtime was spent doing homework. I had to prepare a presentation on a book that represented how we could improve schools. My choice was, Eight Habits of the Heart: Embracing the Values that Build Strong Families and Communities, by Clifton L. Taulbert.

“So while I’m working on this project, I’m sitting in the midst of family, laughing, crying, telling stories and doing what we do. We were a metaphor for the book. I had chosen the book long before there was a need for the trip, but the time with family gave me an even deeper realization that I was on the right track with my decision. Needless to say, my class presentation was filled with emotion and I’ve never looked at my visits ‘home’ in the same way.”

It is with certainty that many Black northern women feel the exact same way as Nancy.