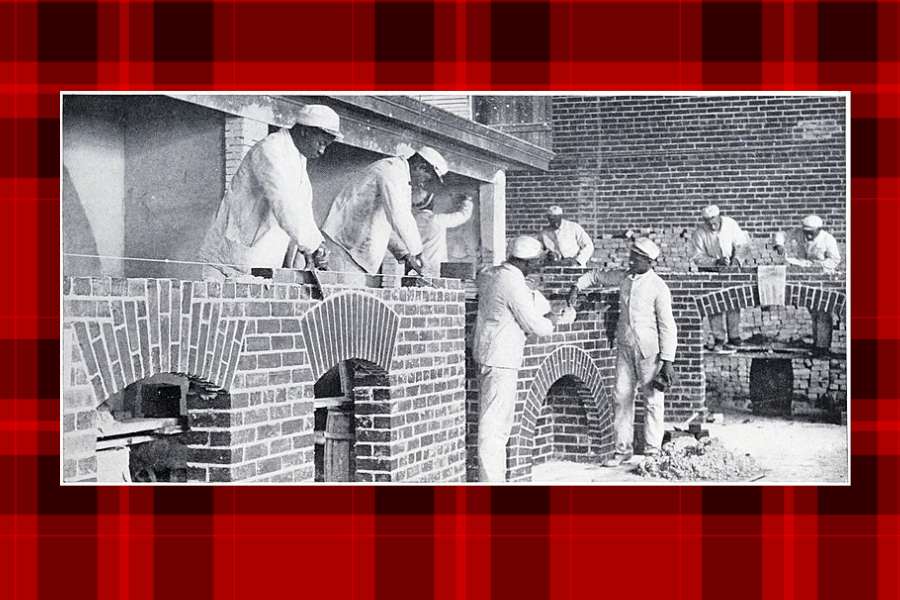

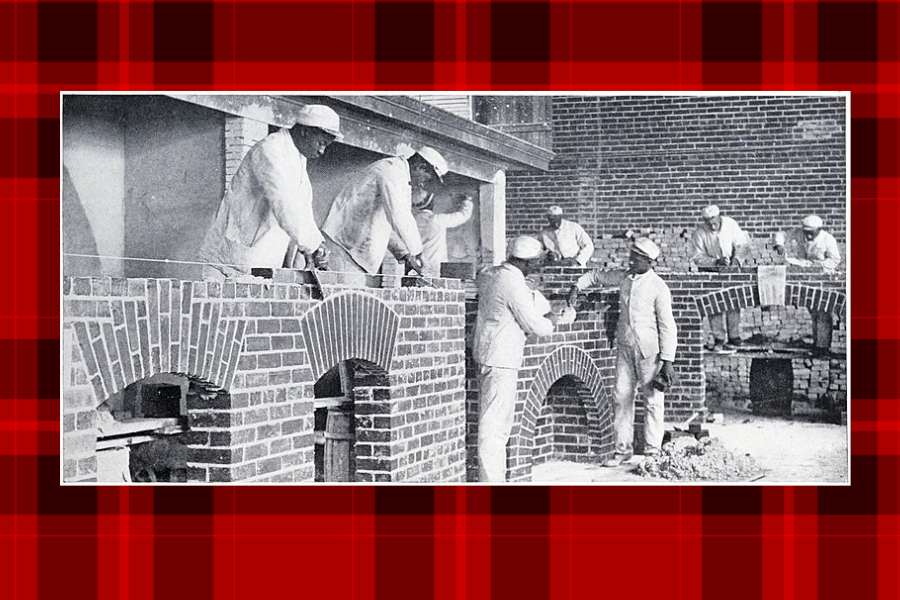

Whatever is left of Black architectural antiquities in the United States, particularly in once-segregated communities in the North and South, is the work of African American brick and stone masons. They brought structure and artistry to the places where Black people worked and lived from the bricks forming streets to the walls of buildings and houses, they often worked in concert with other Black artisans and craftspeople to bring life to neighborhoods.

Before then, enslaved craftspeople contributed to the building of a nation. Skilled laborers from Africa built plantation houses, entire business districts and even the landmarks that remain standing in our nation’s capital Washington, D.C. Former first lady Michelle Obama received harsh criticism for stating that the White House was built by enslaved laborers though she was correct. The White House website states, “Enslaved African-American quarrymen, sawyers, brick-makers, and carpenters fashioned raw materials into the products used to erect the White House.” The work of enslaved brick masons can be found on the grounds of universities like the University of Virginia, Georgetown and George Mason. At UVA alone, “In 1825, fifteen slaves manufactured between 800,000 and 900,000 bricks to be used in the construction of the Rotunda, a domed building that was the focal point of the Academical Village and would serve as the university’s library.”

This brick, found at George Mason’s Gunston Hall in Fairfax County, bears the indentations of fingerprints, likely those of one of the enslaved workers who created the bricks used in the construction of the 1750s Georgian home.

Credit: Virtual Curation Lab, courtesy of George Mason’s Gunston Hall

In Youngstown OH, Oscar and Elisha Boggess, Virginia born brothers to an enslaved mother, worked as bricklayers and stonemasons. Oscar quarried sandstone on his property. P. Ross Berry and his sons were also master bricklayers and masons in Youngstown. The Boggess and Berry brick and stone masons were responsible for building houses, churches and more in the city.

Frankfort KY’s Harry Mordecai purchased his freedom and that of his family using his skill as an enslaved brick mason. He also amassed a considerable fortune doing the work.

In 1865, Blacks were allowed admittance into The Bricklayers and Masons’ International Union, which had an anti-racial discrimination clause in its constitution. While the work was plentiful, opportunities were often denied in the form of soft discriminatory practices, such as white counterparts refusing to work beside them though a fine could be imposed for doing so. Black bricklayers and masons, to survive, often took non-union jobs at the peril of suspension from the Union.

Portrait group of African American Bricklayers union, Jacksonville, Florida. , 1899. [?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705784/.

Over the years, African Americans formed their own unions in cities such as Jacksonville FL and Montgomery AL.

Montgomery Black Bricklayers Hall, which served as a hub for Montgomery Bus Boycott organizers

Photograph by Evelyn D. Causey courtesy of the Alabama State Historic Preservation Office

The brick artistry of James Vester Miller can still be found in Asheville NC. During the 1880s and early 1900s, Miller & Sons Construction built churches and commercial buildings during the late 1880s and early 1900s throughout Buncombe County. His work in the Black community can still be seen on a walking trail created by his granddaughter Andrea Clark.

YMI (Young Men’s Institute) at the intersection of Market and Eagle Streets in 1905. Left to Right: Mrs. Maggie Jones (wife of YMI pharmacist Henry E. Jones); fourth from left, Edward W. Pearson, Sr.; fifth from left, Dr. Lee Otus Miller (son of James Vester Miller); standing behind Dr. Miller, Stanley McDowell; far-right (hat in hand), James Vester Miller. Credit: James Vester Miller family.

Around the same time James Vester Miller was building Black Asheville, Jake Dillard built the first Black school in Tulsa’s newly-formed Greenwood District as well as having his hand in the building of many other Black dwellings and commercial properties. The African American trade union, Hod Carriers 199, provided the bricklayers, masons, plasterers and other tradespeople that built Greenwood’s churches, schools, apartment buildings, hotels and other buildings in the business district. Some of those same men were instrumental in the rebuilding of Greenwood after the massacre.

Old Bull, looking southwest, 1905. Durham’s oldest standing building built in 1874 was built with Fitzgerald bricks.

(Courtesy Duke Manuscript Collection / Digital Durham & Open Durham)

Ad for R.B. Fitzgerald’s brick manufacture, from “Chas. Emerson’s North Carolina Tobacco Belt Directory.” Edwards, Broughton & Co., Raleigh, page 135.

The most illustrious of Black brick masons, layers and makers would be Durham NC’s Fitzgerald brothers – Richard and Robert – who built a literal empire on bricks. Though their bricks and brickwork can be found throughout the city, the Fitzgeralds’ best work could be found right where they lived and worked: the Hayti neighborhood and on Black Wall Street. Richard’s niece and Robert’s granddaughter activist, Episcopal priest Pauli Murray grew up in a home built by Robert and now it is The Pauli Murray Center as well as a National Historic Landmark site in Durham, North Carolina. Behind the property is the Fitzgerald Family Cemetery. Richard Fitzgerald was the first president of black-own Mechanics and Farmers Bank.

Fitzgerald bricks found at Hayti Heritage Center, Durham

St. Joseph’s African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church at 2521 Fayetteville Street in the early morning in Durham, North Carolina.

The greatest pride of Black brick masons, like the ones mentioned above, could be found in their own neighborhoods. Wherever there were thriving Black sections of town or lands of promise, the craft of Black bricklayers and masons represented self-sufficiency and economic empowerment. Those bricks also told and tell a story of strong foundations and resiliency.

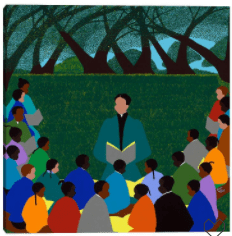

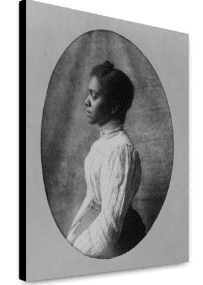

Unknown, book in which the image is published in was edited by W. N. Hartshorn and George W. Penniman., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

19