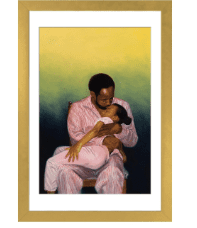

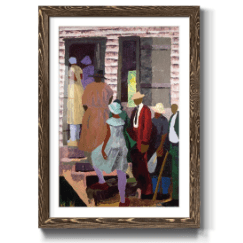

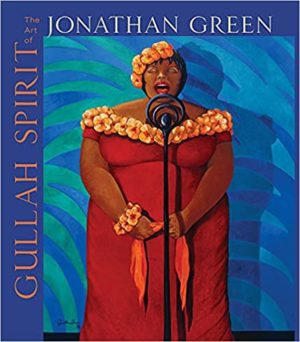

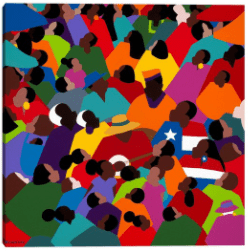

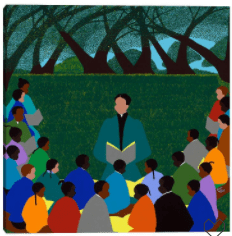

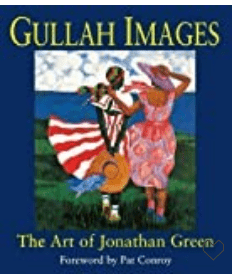

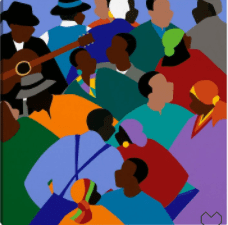

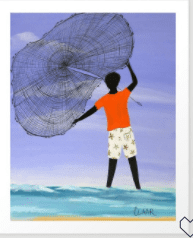

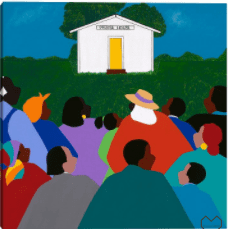

Gullah panache. There is such a thing. The vibrancy of Gullah-Geechee culture found in the paintings of Jonathan Green, which tell stories of a vibrant lifestyle filled with joy, food and whimsy are all about the color and freedom that is both within the people and surrounding them.

We sometimes miss the way in which Green artistically tells a story of the culture’s elegance and culturally respectful sophistication that includes the language and ways of a people, who’ve contributed much to an American story. The late Alberta Wright (1931-2015) could easily be the subject of one of his paintings. She brought lowcountry grandeur from her beginnings in Berkeley County, South Carolina to New York City, where she left an indelible impression on the city with her vintage/antique business and her restaurant, Jezebel.

Alberta was born in 1931 to sharecropper parents in Pineville, SC. She learned to cook watching her mother Annie, a domestic in the homes of wealthy white families. After giving birth to twin sons – Donald and Ronald – Alberta Wright hightailed it to New York City, working in a variety of jobs to save money to send for her children as well as care for them afterwards. According to her New York Times obituary, “she once served chili to Malcolm X and was a regular at West African diplomatic parties, where she learned of new foods and spices that she later used in her kitchen.” She was also active in the Civil Rights movement.

Brad Johnson, restaurateur and the owner of Post & Beam Hospitality Group and longtime friend of Alberta Wright, wrote an amazing tribute to his friend for the James Beard Foundation’s newsletter. In that tribute, he wrote of Alberta’s father,“Edmund, augmented the family business of sharecropping with hunting and fishing. According to Alberta’s beloved son, the actor Michael Wright, Edmund also had a side hustle. ‘Edmund kept a still deep in the swamp where he manufactured his own corn liquor which he sold and drank during the Depression.’”

Therein lies Alberta Wright’s inheritance: Her mother’s cooking, her father’s work ethic and both parents’ enterprising ways. The rest can be attributed to her own sense of adventure, creativity and drive. They say if you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere. But truth told, if you can make it in the lowcountry, New York can be a breeze. And like many others, Alberta joined the second wave of The Great Migration northern bound, arriving in NYC in 1947.

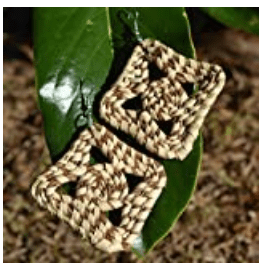

After 20 years of working for others, Alberta Wright opened a vintage store, Jezebel, that New York magazine (Sept. 9, 1974) featured in a curated list of unique shops. She sold complete period wardrobes for men and women. In the article, her meticulousness is noted. “Ms. Wright is emphatic about the clothes’ wearability…,” continuing with a mention of her washing and ironing each item before putting them on her sales floor. Nine years after that article, she opened Jezebel the restaurant, and decorated the interior using many of the items she once carried in her shop.

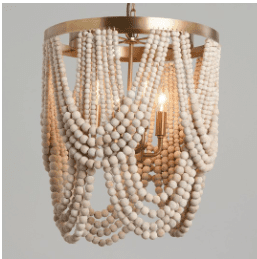

Jezebel, Interior view

A few months after its opening, New York magazine’s “insatiable critic” Gael Greene used great detail to describe Jezebel’s service, food and interior. Sadly, Greene had no cultural context for much of what she ate or what she saw. For example, much of Jezebel’s menu were items common to lowcountry cuisine: she-crab soup, chicken livers, red snapper with cornbread oyster stuffing, southern fried catfish strips, shrimp creole with white rice and okra, bread pudding, sweet potato pie and banana pudding. There were other items as well, but Alberta’s menu was more than soul food, it was distinctly lowcountry or Gullah. For all of the things Greene found inconsistent or puzzling about the food and décor, she ended her review this way:

Greene didn’t know or mention that the courting swings bolted from the ceiling or the silk piano shawls draping the tables and hanging from the ceiling or the art by Black artists with the faces of Black people, Andy Warhol’s art, and the Baccarat chandeliers were all intentional choices based on the homes Alberta’s mother worked in and the touches her mother replicated in her childhood home. The décor was also evidence of Alberta’s refined sense of style, which Greene understood.

Jezebel (located in Hell’s Kitchen) remained busy with a customer base of the known (Roberta Flack, Hillary Clinton, Stevie Wonder, Andy Warhol, Yoko Ono, Pauletta and Denzel and many more) and the unknown that Alberta made feel every bit as special as the knowns. She offered southern hospitality in the most authentic way.

Alberta had other ventures, including Piece of Chicken, a walk-up restaurant attached to Jezebel’s kitchen. Jezebel closed in 2007 and Piece of Chicken in 2010, but Alberta and the restaurant remain important stars of NYC’s culinary and hospitality histories, its black history and women’s history.

Johnson wrote, “The New York Times’s food critic Bryan Miller awarded Jezebel two stars, calling the restaurant ‘one of the most intriguing settings in New York City.’ One would be hard-pressed to identify a Black-owned and -operated restaurant that had previously even been reviewed by the Times, much less awarded stars.”

Alberta Wright was a woman compelled to create a world just like she created the life she desired in New York. She opened Jezebel with no backers or investors, no marketing and business plan. She executed a dream, a successful dream that served NYC well for about 25 years. And she did it with Gullah panache.