The recent passing of our icon and beloved lifestyle expert Barbara “B.” Smith has left us wondering and wanting for more in the heritage of hospitality as expressed by her. Barbara Smith was very clear about who and what inspired her work. She told New York magazine, “Martha Stewart has presented herself doing the things domestics and African Americans have done for years … We were always expected to redo the chairs and use everything in the garden. This is the legacy that I was left. Martha just got there first.”

Before Martha and B. Smith there were Black women who expressed hospitality at home, in books, on TV, and in their communities.

Our heritage as lifestyle and hospitality “experts” began with the arrival of the first Africans in Point Comfort, Virginia in 1619. Isabella is the first captured African to work as a servant-domestic in the home of Captain William Tucker. Another indentured servant Angela arrived in Jamestown, Virginia from Angola in 1620, and worked as a domestic-servant in the household of William Pierce. As slavery progressively became law in the colonies, and then the United States, the role of the Black woman as a domestic expanded according to two primary factors: the stature and wealth of the household served and the number of enslaved bodies available to perform farm or plantation duties as well as duties inside the owner’s home. Enslaved men were often the managers of the household “staff” comprised of other enslaved people, but it was Black women who were charged to perform the duties related to hospitality:

- The day-to-day cleaning of the household, including

- The regular maintenance of the household from the cleaning and storage of dinner linens and silver service

- Day-to-day cooking for every meal and cooking for special occasions

- Weaving textiles, spinning yarn and threads, and sewing for the household and for the staff, and sometimes for every enslaved person on the grounds

- Tending to flower and vegetable gardens

- Candle-making and more

Whether enslaved in rural areas or in urban areas, enslaved women as domestic workers laid a groundwork that enabled a good number to survive and thrive post-Emancipation, using a precision-like skillset to create work for themselves. The first two Black women cookbook authors Abby Fisher and Malinda Russell took knowledge as cooks and created businesses. Russell was a baker who would also work as a laundress and owned a boarding house as well as a bakery. Abby Fisher was formerly enslaved in South Carolina and would operate a successful pickle manufacturing company in San Francisco. An interesting aspect of their books is that the reader not only receives recipes but suggestions on how to serve, which is a major part of hospitality.

The history is solid and involves independent food businesses and a history of working in hotel and restaurant hospitality. Black women took the same knowledge and applied it in churches, their homes, and in great careers.

Like New Orleans’ Lena Richard. Lena Richard is an amazing example of taking a legacy of hospitality and domestic service and turning it into a career as a lifestyle expert. It has been said that Lena was Martha Stewart before there was a Martha Stewart. Richard graduated from culinary school – the renowned Fannie Farmer Cooking School in Boston – in 1918. At the height of her profession, Lena Richard was a cooking teacher, chef, caterer, restaurateur, frozen food entrepreneur, cookbook author, and TV cooking show host in Jim Crow New Orleans.

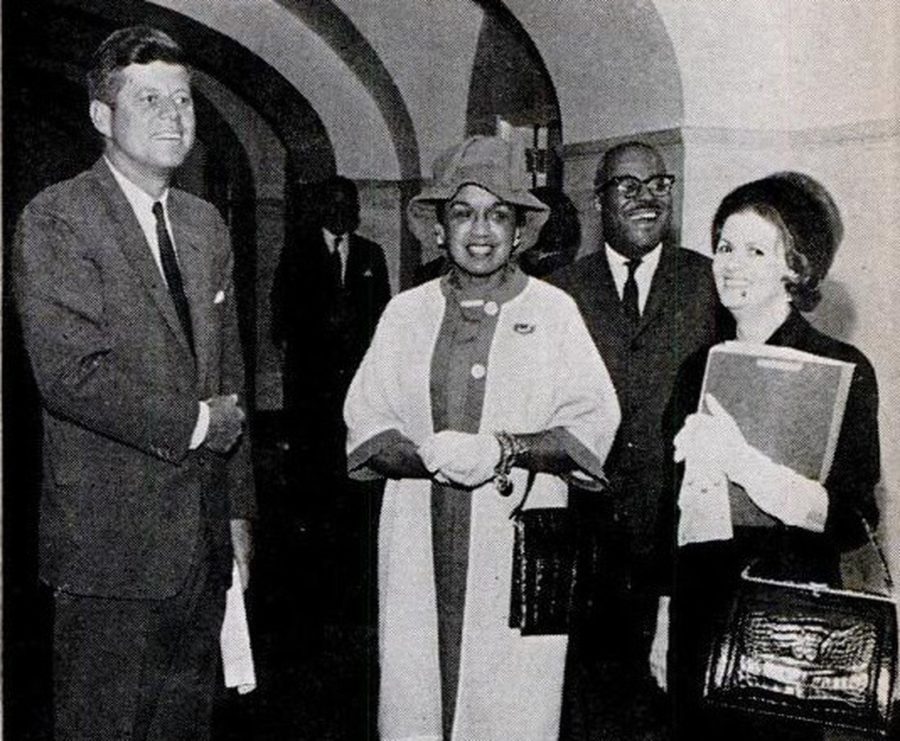

Around the same time, a new magazine for African Americans – Ebony – employed a home economics teacher to be their first food editor (and the first African American food editor of a publication) and write a monthly column, “A Date with a Dish,” that featured recipes, household tips, and home entertaining solutions. Freda DeKnight enjoyed a national platform that led to a cookbook published by Johnson Publishing, TV program segment demos, and she toured with Ebony Fashion Fair, which she helped found and organize. DeKnight became the lifestyle expert who had a finger on the pulse of black celebrities and food, black chefs and restaurateurs, and black homemakers.

Richard and DeKnight presented and represented an image of Black women who cared about their homes, giving great parties, cooking good food and that aspired to have their versions of the American Dream. They did that while elevating black heritage. They also paved the way for Barbara Smith, who in turn opened doors for women like Phyllis Bowie who would go on to host “Life with Soul” on TV ONE, Pattie Labelle who had a TV show on TV ONE and has since signed licensing deals for food products, books, and her own Cooking Channel TV show. Laila Ali (Home Made Simple), Justina Blakeney (Jungalow®), Carla Hall and a host of new and wonderful interior designers, lifestyle and food bloggers are carving new paths that include product licensing, books, TV, webseries, and more.

Hospitality is the legacy left to all of us by the elders who had no choice but to redo chairs, set tables, cook food, and prepare other women’s homes for entertaining guests. Through them we developed a fondness for good china, tablecloths, and above all else, making people feel comfortable in our homes. They are the real stars of this story.