Black women have always cared about a well-appointed and managed home that includes regular cleaning and maintenance to having all of the proper homegoods necessary for entertaining, cooking nourishing meals, and more. Most of what we have learned has been passed down through the generations, particularly from foremothers who worked in bondage or as domestics in the homes of others. The Rosenwald Schools and HBCUs like Tuskegee offered home economics and domestic science courses for young women who were preparing for teaching jobs but also preparing for home lives – married or not. As antiquated as the notion of managing a home is, it is often misunderstood.

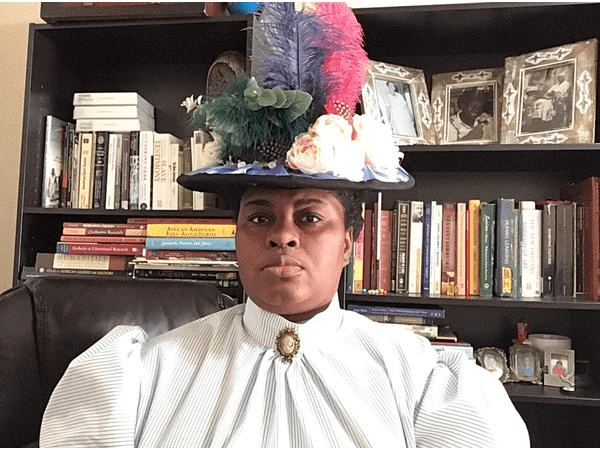

New Orleans-based educator and historical interpreter Gaynell Brady says, “I’m big on getting rid of that stereotype that Black women neglected their own homes and neglected their families; like they cared for other people’s families more than their own. That’s just not true.”

As the founder of “Our Mammy’s,” an organization that provides educational services such as virtual tours, field trips and presentations to museums and schools, Brady endeavors to make people comfortable with and embrace their personal family histories. She does so from the lens of her own grandmothers, who like many of ours were hardworking women tasked with jobs and managing a home.

“They would get up early in the morning to do the things needed to not neglect their own homes before going to care for others’ homes,” says Brady.

The focus was on the comfort to function on a day-to-day basis, ensuring everything was in place and everyone had what was needed to live, work and even play. The well-being of a household’s inhabitants depended on an orderly household, which did not cease to be true even as more and more Black women entered the workforce. In fact, it became more important given the limitations of time.

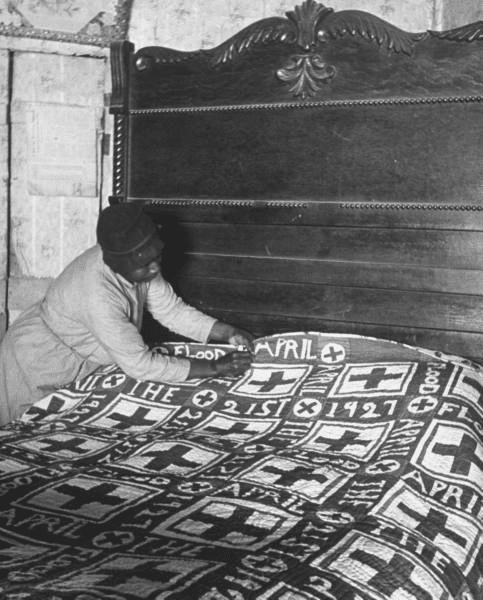

Domesticity and comfort in slave quarters was very important though the late W.E.B. Du Bois criticized what he thought to be unhygienic conditions and unsophisticated living where slaves resided, expressing dismay that the enslaved had not picked up the habits of their owners. Archaeologists, anthropologists and historians have since documented the importance of home among enslaved women, including cleanliness rituals and managed home lives. Enslaved women had their own standards of making a home, which often spilled over to their service to the ones they served.

At the turn of the last century, Black newspapers and magazines like Half-Century Magazine for the Colored Home and Homemaker featured regular columns and articles that offered Black women of the era information on entertaining at home, etiquette, cleaning schedules and choosing home décor. For example, writer Lucille Browning contributed a piece “Making the Guest Room Attractive” that advised on choosing the right linens and on how to make curtains, which appears on the same page as an article about World War I. Black wives and mothers not only cared about home from a domestic standpoint, they also cared about activism in our communities.

Though some of the practices are no longer essential, there are those that remain, especially in the practices of the descendants. Brady muses, “I think about the cleanliness of my grandmother and her family…my grandma had this thing about making sure the porch was spotless. The way in which we had to scrub that porch down on early Saturday mornings. If you spilled something on that porch it had to be cleaned up immediately.”

Brady has a cleaning ritual she learned from the women from Glynn, Louisiana, on her dad’s side. “Clean from back to front and top to bottom. You don’t start at the front door, because you want to escort the bad luck out the front door or forward,” she says. After all of the cleaning, her dad would sprinkle Florida Water throughout the house.

Murray & Lanman’s Florida Water is a multi-purpose product that can be used as a part of a cleansing, protection and good luck ritual in the home. Some people use it in their laundry or as an astringent on bug bites or as an air freshener. Brought to market in 1808, Florida Water was found in the homes of the well-heeled and in the homes of many southern Black women.

Other products from a certain era that some women still use are Murphy’s Oil Soap (for cleaning woodwork and wood floors), Argo Gloss Laundry Starch (starching laundry or to degrease), Mrs. Stewart’s Bluing (laundry brightener), scouring powder (Ajax, Comet, Bon Ami), silver polish and anti-dust sprays like Endust and furniture polish such as Pledge.

African-American Women with Brooms of Bambusa (Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration).

The cleaning rituals that existed in those days involved a tedium that would probably drive most working mothers crazy today. A few of those activities involved scrubbing walls, cleaning baseboards and the moulding on walls and around doors, dry-cleaning drapery, beating rugs outdoors, and washing windows – inside and out. There was also silver polishing, taking the tarnish off of copper pots and other metal objects, and washing table linens. Carpet was cleaned and furniture upholstery had to be cleaned and vacuumed. These were maintenance chores.

Laundry day at Oak Ridge during Manhattan Project, Oak Ridge TN, 1940s. National Park Service

If, as children, we had to get up early to perform chores, it was most likely to avoid the heat of summer days. And it was to make room for all of the errand-running and activities busy mothers had to fit into a Saturday or Sunday, when some observed the Sabbath.

Though a few Black women could afford to have ‘help’ come into their homes to assist with chores and babysitting, most had to do it themselves while juggling family, jobs and all else life threw at them.

Gaynell Brady believes that the way our foremothers cared for their homes was an expression of love. She says, ““The presence of those matriarchs remains in the ways we care for our own homes, including in some of those rituals.”

To learn more about Gaynell, visit her website and follow her on Instagram. You can also listen to her on Genealogy Adventures as she discusses genealogy as a practice. And you can read about her family traditions on the Madam Ancestry blog.

Photos of Gaynell Brady via OurMammys.com

2