Peas, peas.

Peas and the rice done done, uh-huh.

Peas, peas.

Peas and the rice done done, uh-huh.

The late historian and folklorist Cornelia Bailey would tell the story of how Gullah-Geechee women, deprived of the rice they planted, harvested and prepared to be sold, would sing a chant as they winnowed the grain. She said, “And when they go with the “uh-huh”, some of it would always drop inside that apron pocket. So when they went home at night when work was over, they had enough rice to feed their families. And without being caught.”

Without being caught with rice that came from Africa and was cultivated using West African rice farming systems to make a huge profit for plantation owners. According to The Rice Diversity Project,

Cultivation of rice in Africa began along the Niger, Sine-Saloum, and Casamance Rivers and archaeologists have uncovered evidence

of rice cultivation 2,000 to 3,000 years ago in these West African regions. Modern West African countries that produce rice are Niger, Senegal, Ghana, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Congo.

The first documented arrival of rice to the South Carolina colony was in 1672. It arrived in a bushel on a supply ship named William and Ralph, which sailed from Great Britain to West Africa before coming to the Americas and the Caribbean, and traveling back by the same passage.

A law was passed in 1691, and rice was accepted as currency to pay taxes. Rice growers and the South Carolina Assembly had found a way to profit from rice. Rice was like gold.

By the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, rice was the chief cash crop of South Carolina. “Carolina Gold” (rice) was sold and exported throughout Europe for a premium price. South Carolina would become the leading producer of rice in North America, and hold that distinction for almost two centuries using the free labor and ingenuity of African slaves.

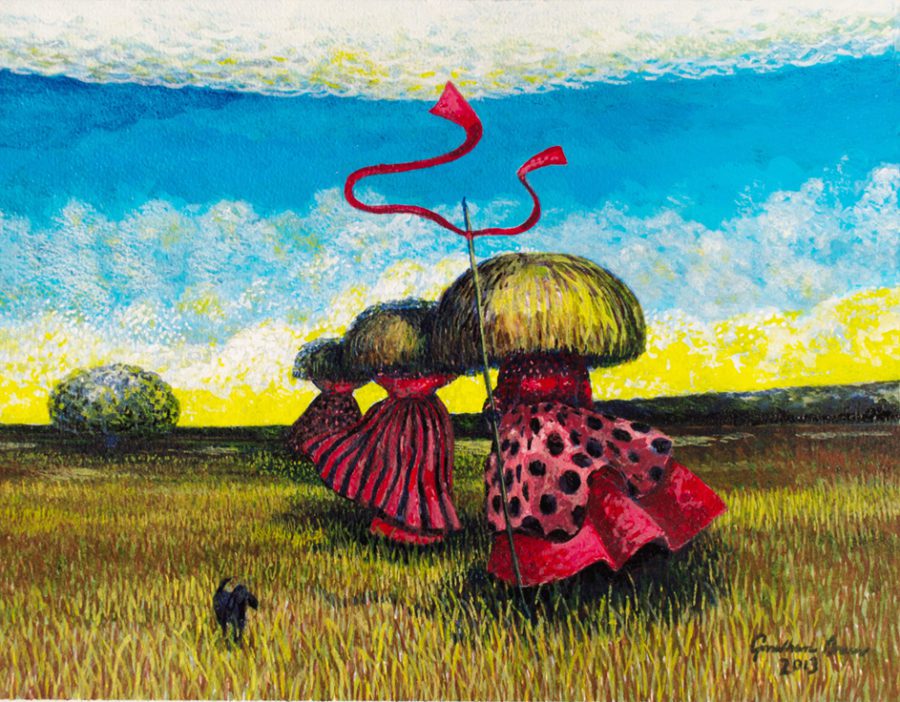

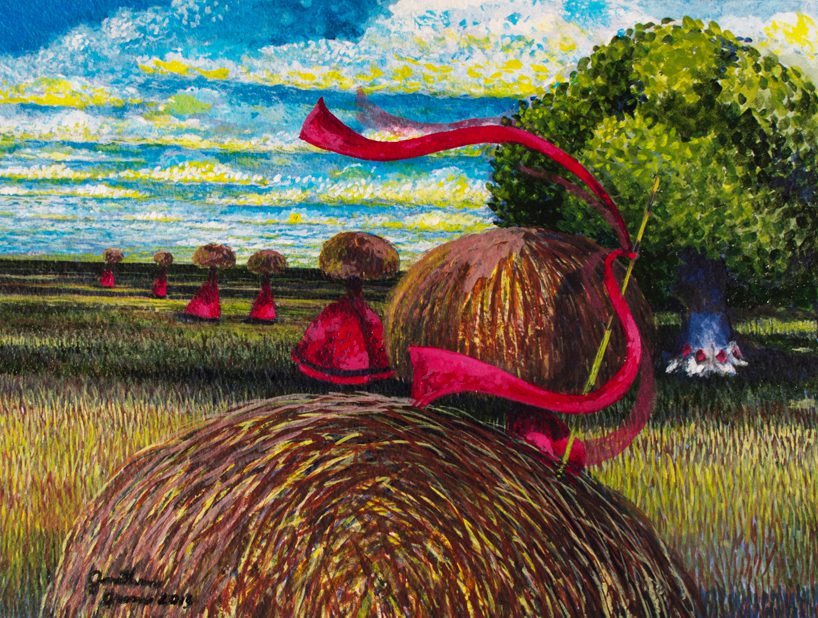

African men cleared the swamps and built dykes, and African women sowed rice seeds. Using their bare feet, the women planted those seedlings into muddy soil employing a toe-heel method. The work was arduous and often threatened the health of the enslaved workers. Swamp areas were mosquito- and snake-infested. Flies transferred dung – human and animal waste – onto skin dampened by the heat and humidity. To say that these were the worst of conditions is an understatement, and the bulk of the work was performed by African women. Cornelia Bailey refers to some of those women above. The women who were told they could not have the rice to feed their families.

No people were as vested in the success of South Carolina’s rice industry than the enslaved Africans, especially women. Their knowledge, craft-making and skilled labor created wealth for everyone but them.

After the Civil War and into Reconstruction, South Carolina’s rice industry took hard blows. It disappeared. The free labor had been emancipated. Freed to choose to stay and create enterprise for themselves and freed to leave.

But the grain that they worked so hard to cultivate remained as a staple in Gullah African-inspired cuisine and as a staple in their diets.The love for rice stretched North America due to The Great Migration and other transitory paths taken African Americans with roots in the South.

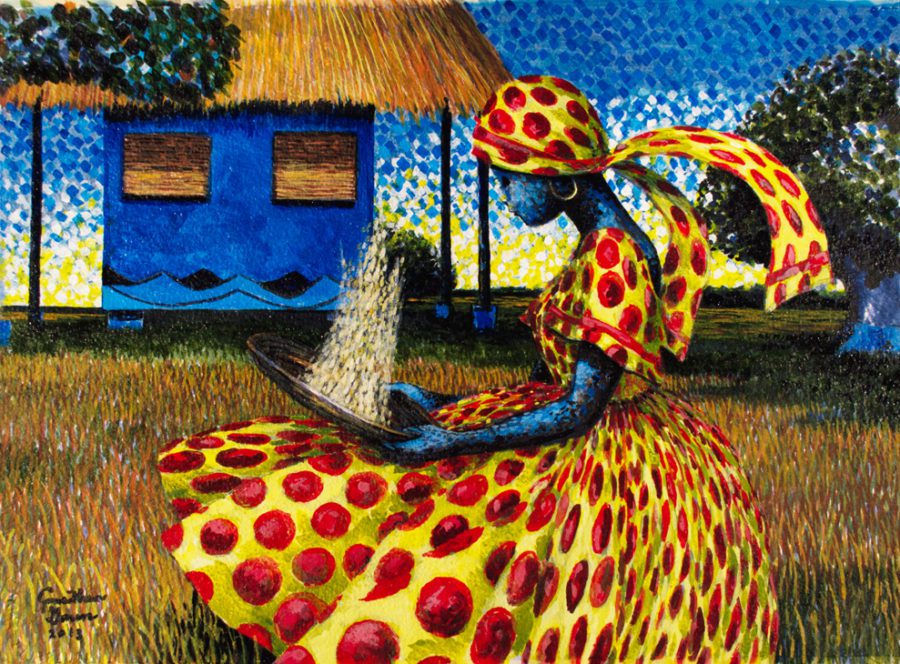

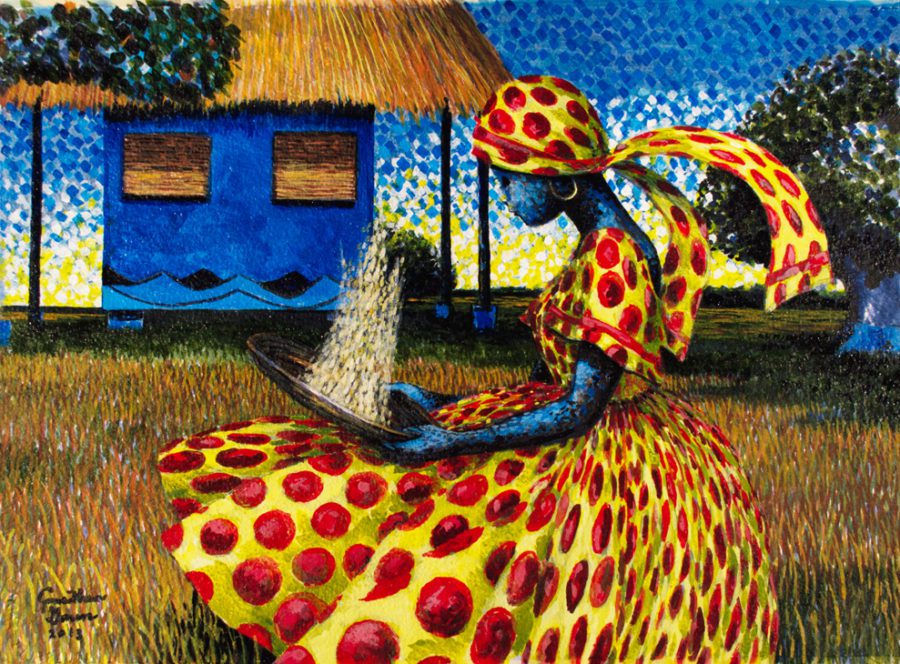

Charleston artist Jonathan Green stated in an interview, “I knew of my grandparents and their peers as independent rice farmers. They grew rice for themselves and to share with the community.”

Green is the founder of The Lowcountry Rice Culture Project. The Gullah artist has been tirelessly re-telling and re-imagining an inclusive story of South Carolina’s rice culture to help people understand the complexities of African American’s relationship to rice. His greatest mission is to create conversations about history, race and humanity by creating forums focused on lowcountry rice culture.

For the late Cornelia Bailey and the very living Jonathan Green, talking about rice culture in the lowcountry is about restoring the dignity of a people, and a people who maintained their culture.

“If you haven’t eaten rice today then you haven’t eaten.”

~ Sierra Leone proverb