During the late 1880s into the early 1900s, before the first World War, the Gullah people of the Lowcountry were in a state of transition. The old rice plantations were all but dust and the land was invaded by rich, white northerners who moved their winter hunting retreats South. A few remained to tend to their seafood estuaries while others ventured North to Philadelphia and New York City to seek greater opportunities. By the Roaring 20s, “…more than 50,000 black farmers left the state, many heading North. Jim Crow laws and racially motivated attacks also drove African-Americans out of South Carolina, especially in the years after Gov. Cole Blease (1911-1915) praised lynching as ‘necessary and good.’” (Coastal Heritage Magazine)

Lowcountry Heritage: A Brief History of Gullah-Geechee Longshoremen

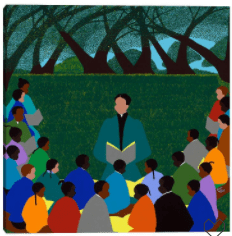

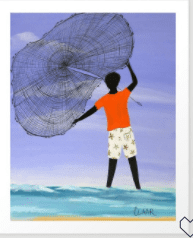

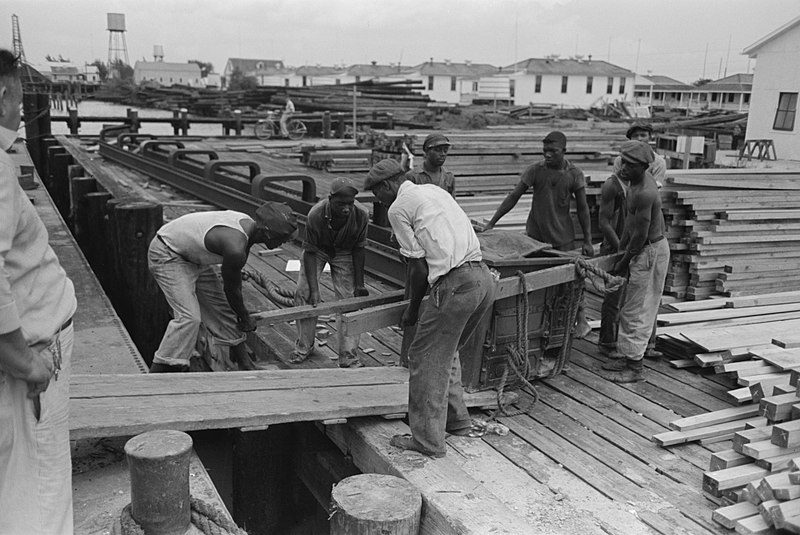

But there were some Gullah men who packed up alone or with their families and moved to the ports of Charleston and Savannah to take jobs as longshoremen. Unlike some skilled trade jobs, the black longshoremen had a history that pre-dated the Civil War back to the Colonial-era, when 3enslaved Gullah-Geechee men were often allowed to take jobs on the docks and wharves. Many like Robert Smalls, the last Republican U. S. Congressperson until 2010, were skilled at almost every part of water transportation working beside white men. Smalls’ skill and knowledge of the water won him the coveted assignment to steer the Confederate’s CSS Planter, a lightly armed Confederate military steamer that he commandeered to escape from his enslavers with other crew and their families. Smalls leveraged his agency to snatch freedom and deliver Confederate guns to the Union or United States Navy. He would live out his life in politics and business, supporting the formerly enslaved as well as advancing education.

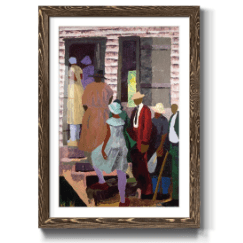

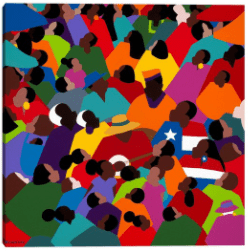

Most Gullah-Geechee longshoremen would not have an illustrious career as Smalls but they would create good lives for themselves, their families and communities. From the northernmost tip of the Gullah-Geechee Corridor in Wilmington, North Carolina to ports in Florida, the enslaved to freedmen to the newly emancipated in the 1860s forged a path that would ultimately include union membership in the International Longshoremen’s Association, the largest union of maritime workers in the United States. Black longshoremen worked alongside immigrants and non-blacks though there were often divisions and a few violent clashes between the groups. In some cities, black longshoremen were driven out of work, often hazed and bullied into performing menial tasks to prove worthiness and accept lower wages. In other cities the predominant number of longshoremen were African American (Mobile AL and New Orleans).

On the Gulf Coast, black longshoremen made a decent wage on the same docks and in the same ports that at one time docked slave ships containing enslaved Africans, most likely ancestors. The hideous reminder most likely propelled many Gullah-Geechee men to work harder beyond proving worthiness to asserting their rights. Not all interactions were violent as in the case of the black Mobile, Alabama dockworkers (where black longshoremen totaled more than 90% of dockworkers) and longshoremen who engaged with white peers in solidarity for union reform in the 1930s. Historian James Maroney wrote, “The ILA organized separate locals for blacks and whites in southern ports, but these locals, out of economic necessity, developed the custom of dividing available work on a fifty-fifty basis. Segregated locals allowed blacks to hold many more offices than they would have had in integrated locals…” In short, southern longshoremen had a voice and some power. The Mobile Benevolence Association, an auxiliary of the ILU, refused to take in white members in an act of maintaining power and safety for its black members.

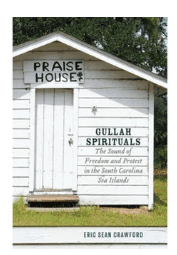

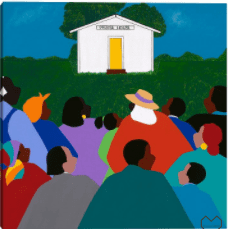

Over the years, Gulf Coast longshoremen and women have been at the front of some very important civil rights campaigns, especially in Charleston. “The Charleston ILA’s tradition of political work dates back to Reconstruction, when the union was founded as an association of newly emancipated waterfront workers. During the first Poor People’s Campaign, the ILA shut down the East Coast, Southern, and Midwest ports in honor of Martin Luther King Jr., following his April 4, 1968 assassination.” – Kerry Taylor, historian, The Citadel

In 2015, International Longshoremen’s Association Local 1422 protested the spearheaded the “Days of Grace” march and conference to protest poverty, inequality and police brutality right after the murder at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. One member of the local lost his son and aunt at Emanuel while another member was the brother of Walter Scott who had been murdered by a police officer. The march was also to honor the “Charleston Five,” union members who had been placed under house arrest nearly 20 years before for protesting to save union jobs at the Port of Charleston. Local 1422 has challenged a number of wrongs, including racism and the effort to take down the Confederate flag at the SC state capitol.

The men and women who work longshoring, like their ancestors, are often subject to some dangerous and life-threatening duties. Longshoring is not a cake job, but it is a job that has purchased freedom, homes and businesses as well as funded causes that have helped generations of Gullah-Geechee people living in The Corridor.

100