In 1988, late Gullah culinary anthropologist and food writer Vertamae Smart-Grosvenor told the New York Times, ”You can’t have a proper funeral without food. When someone dies, the food, the spread, the feast has to be right so people will say, ‘She had a proper send-off.’ Otherwise they’ll talk bad about it.”

Funeral food comes with a narrative similar to other food narratives in black culture. It tells us something about the people who have died and it tells us something about the living they left behind. Within African American culture, especially southern cultures, most funeral food traditions are rooted in the West African traditions that arrived here with the enslaved.

Depending on the enslaver and location, the enslaved often hosted elaborately-planned funerals for those in their community. Most funerals took place at night as not to interfere with their duties during daytime. Some West African beliefs about death meant that the deceased would return to their homeland, so the celebration of their life that involved great care of their body and kin was termed a homegoing. A benevolent enslaver would allow enslaved relatives and friends to visit for these occasions, so food was a matter of sustenance for traveling guests and also a form of fellowship. The rare enslaver provided extra food allotments such as meat, rice, corn meal, and whiskey or rum. The foods prepared could include corn pone, sweetmeats, fried fish, and most likely pot meals such as a stew or gumbo or a pepper pot to accommodate a large volume of people, nothing fancy but it was plentiful and welcoming. A good meal said, I am caring for you in our departed’s stead.

Photo Credit: Chantilly Lace Photography

Post-emancipation, remnants of African funeral traditions remained as Black-owned funeral parlors and mortuaries became a norm in black communities. Though body preparation was now left up to the professionals, the food remained the responsibility of the departed’s community. The mainstay from African funeral and funeral food tradition was the care of the departed’s body and care for the departed’s people.

The same is true in the 21st century. Few know you never arrive empty-handed at the home of a shocked, newly mourning family. You bring food to give them one less thing to think about as well as to feed the people coming in and out of their home to sit with them. Sitting food can be anything from a bucket or box of fried chicken with sides to a store-bought cake to ice to soda pop to a pot of greens or green beans to a pan of spaghetti. Black people will bring whole turkeys and hams with Thanksgiving Day fixings. A bereaved family will receive all of that and more from the time they start accepting visitors to the day of the funeral. Sitting food feeds the family and their visitors, but it also feeds the trusted few who come in to take care of the family and their home while arrangements are being made. Sitting food completes the circle of comfort until the repast.

The post-funeral meal is often called the “repass” though it is actually a repast or feast. Technically, a repast is anything the bereaved family wants it to be from more of the same sitting foods to foods specific to their cultural and religious observances. The repast can run high or low, formal or informal, inside and/or outside, quiet or loud, and somber or raucous, but it is always familial. Etiquette dictates that the family pays for the repast to say thank you for sitting with us, thanking you for loving on us, and thank you for celebrating our kin. Often, however, the departed’s circle of affiliations, from fraternity and sorority groups to their church to their union, will sponsor the repast as a gift.

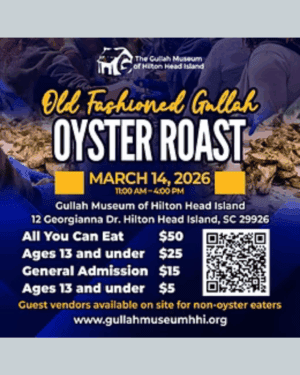

Southern funeral food traditions are perhaps the standard for quality. Bringing something store-bought can be limited to ice and beverages while the food presented to bereaved families is prepared from scratch or as close to scratch as possible. It can come from a home cook’s kitchen or her caterer. In Gullah culture, for generations, the practice of saraka or cooking a funeral meal as a group continues as women gather in kitchens and men at grills to lovingly prepare food for a family to eat as an act of fellowship now and later.

Sending the deceased off with anything less is sacrilege. In the same manner as our African ancestors, the focus is on caring for the memory of the deceased by caring for the deceased’s people. The menu will contain fried chicken, potato salad, macaroni-n-cheese, homemade cakes, pies and rolls – the expected fare to feed an influx of guests. But there are a few things like a fresh garden salad made with cucumbers and tomatoes, okra, oyster and shrimp dishes, and pot and casserole dishes that are the most reminiscent of African funeral food tradition.

Funeral food fare is as vast and extensive as the black southern foodways. In Appalachia, smothered chicken and rice could show up in some hands. Pork chops and purple hull peas could be on a buffet in Northern Louisiana. Northern kin could possibly turn their noses up at some southern funeral foods like hog’s head cheese, chitlins, black-eyed peas, red rice, she-crab soup, tea cakes, and funeral grits (cheesy grits casserole). Down South those foods imply thoughtfulness for the deceased, their family and memory. Comfort.

To paraphrase Vertamae Grosvenor, you do not serve food with bad vibes and dead food has bad vibes. Southern funeral food is alive and intended to lift the spirits of mourners. As the last visitor is sent off, there is some solace to be found in savoring a bite of your aunt’s banana pudding or your cousin’s cornbread dressing with a side of potato salad. You do not have to like the occasion to admit loving the food and the gift of it.

I love the description of all the food that would come in during a funeral time it brought back so many memories even though it would be a sad occasion